Ever since the early 1900s, head transplantation has captured the imagination of scientists and the general public. Today, Dr. Jennifer Markowitz, MD discusses the possibility of human head transplants, the massive obstacles in the way, and whether the surgery should ever take place.

The Most Revolutionary Surgery Ever Attempted?

It would be a revolutionary surgery, perhaps the most revolutionary surgery ever attempted. As reported in People.com, Italian neurosurgeon Dr. Sergio Canavero planned to transplant the head of 33-year-old Russian Valery Spiridonov onto the spinal cord of a donor body.

Spiridonov has Werdnig-Hoffman disease, which causes progressive loss of muscles and nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. Believing this was his only option for improvement, he signed up for the surgery in 2015. The procedure was scheduled for 2017, then delayed while Canavero made further preparations. Meanwhile life did not wait for Spiridonov.

In 2017 he married Anastasia Panfilova, a computer expert, with whom he now has a healthy 5-month-old son. Spiridonov also has his own company. With his condition stabilized and having found love, Spiridonov decided to pull out of the head transplant surgery. Meanwhile Canavero said he’d find another volunteer. (Source: People.com)

Is a Head Transplant Possible?

In a 2017 experiment that seems right out of Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein,” Chinese doctors conducted an 18-hour operation in which they claimed to have achieved a head transplant using two recently-deceased cadavers (Source: People.com).

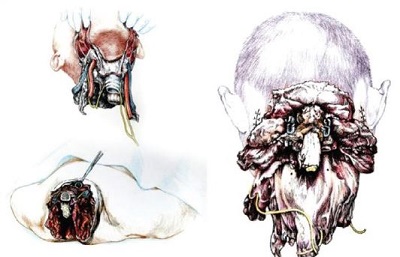

Source: Ren X, Li M, Zhao X, et al. First cephalosomatic anastomosis in a human model.

Surg Neurol Int. 2017; 8: 276.

Even if this operation was a success, it doesn’t answer the question as to whether the procedure would work in living individuals. Perhaps the greatest obstacle to success of a head transplant in living humans is the fact that the spinal cord from the donor head would need to be connected successfully with that of the recipient head. Unlike nerves in the arms and legs, nervous tissue within the spinal cord does not regrow after an injury.

Although there has been a great deal of research in this area, thus far no doctor or scientist has successfully achieved total repair of a severed spinal cord in humans. (Source: Scientific American: Repairing the Damaged Spinal Cord; Journal of Medical Ethics Blog: The Real Problem With Human Head Transplantation)

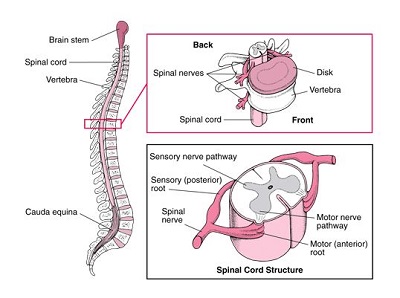

The spinal cord has a distinct structure, consisting of grey matter, or the bodies of nerve cells, and white matter, or the wires nerve cells use to communicate (known as axons). The grey and white matter are involved in sensory and motor functions, as well as autonomic functions such as the fight-or-flight reflex. The spinal cord also contains glial cells, which support the functioning of grey matter nerve cells. One type of glial cell, the oligodendrocyte, produces insulation that helps the axons send signals faster. (Source: Scientific American: Repairing the Damaged Spinal Cord)

Severing the spinal cord has a variety of damaging effects. First there is the injury to both grey and white matter. Then, over time, the damage spreads to levels above and below the place where the cord was initially cut. Injured axons disintegrate or stop functioning due to a loss of insulation, and a cyst, or fluid-filled hole, develops where the damaged cells used to be. Then glial cells grow excessively, forming scars. All of this prevents axons from regrowing. At the same time axons, blood vessels, and nerve cells release the chemical glutamate, which over-excites and damages surrounding healthy nerve cells. (Source: Scientific American: Repairing the Damaged Spinal Cord)

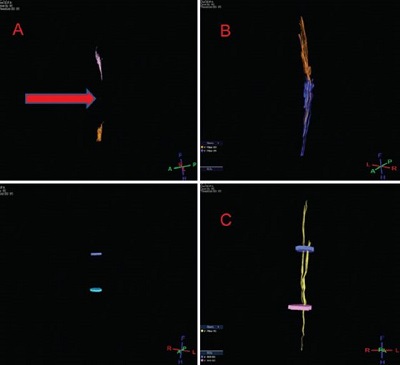

Despite this daunting picture, Dr. Canavero and Chinese surgeon Dr. Xiaoping Ren recently published research in the journal Surgical Neurology International in which they claim to have repaired the severed spinal cords of monkeys and dogs using a substance known as polyethylene glycol, or PEG. They provided what they claimed was video evidence of the monkeys and dogs walking after their spinal cords were severed.

While these results could be encouraging, it’s important to keep in mind that they have not been reproduced by others. The scientific world remains skeptical, especially because the research was not done in humans, and because it was geared towards the development of controversial head transplants. (Source: USA Today)

Imaging showing the severed spinal cord of an untreated dog on the left and, on the right, those of dogs treated with PEG after their spinal cords were severed. (Source: Ren S, Liu Z, Kim C et al. Reconstruction of the spinal cord of spinal transected dogs with polyethylene glycol. Surg Neurol Int. 2019; 10: 50.)

Currently Canavero is planning to perform his first head transplant in China, due to restrictions from the medical communities in Europe and the United States. He anticipates needing dozens of surgeons and other specialists, at a cost of up to $100 million. He has said he plans to use the disease-free head of a donor matched with a brain-dead patient’s healthy body. The donor head would be cooled to protect it from death before it was attached to the body.

Canavero stated that he would sever both donor and recipient spinal cords at the same time with a diamond blade. (Source: USA Today) While severing and re-attaching the spinal cord immediately might prevent some of the later effects of injury, it would not prevent damage from phenomena such as glutamate over-excitation. It is not clear how Canavero would surmount this and many other hurdles involved in the repair of the human spinal cord.

Should Head Transplants be Allowed?

Even if head transplants were possible, the question arises, should they be allowed? As reported on People.com, Dr. Hunt Batjer, then president-elect of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, told the Independent in 2015, “I would not wish this on anyone. I would not allow anyone to do it to me as there are a lot of things worse than death.” Since no one has successfully repaired a severed spinal cord in humans, there is great doubt as to whether the procedure is technically possible. The effects on the head donor simply cannot be foreseen.

Given the likelihood that the patient would die or suffer extreme physical and psychological injury, attempting to perform a head transplant should be considered completely unethical.

Numerous bioethicists and other experts have stated this. However, although there are several ethical codes that this procedure would violate (such as the Nuremberg code and the Hippocratic Oath), they cannot be internationally enforced. Thus, Canavero will likely proceed with his grisly work in China. It remains to be seen if he achieves his goal. (Source: Journal of Medical Ethics Blog: The Real Problem with Human Head Transplantation)